By Doug D. Sims

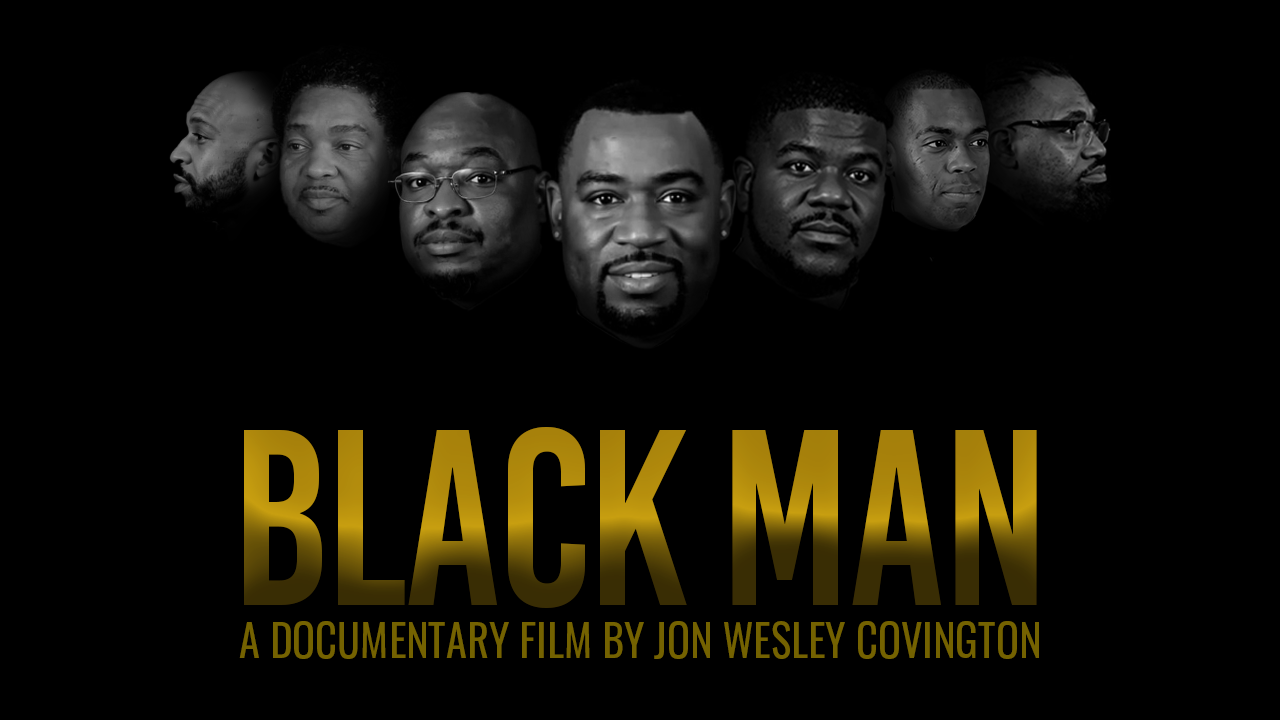

Jon Covington has always been a storyteller. Whether behind a radio mic, a television camera, or a film lens, his work has carried the same quiet consistency: patience, intention, and a deep respect for human truth. But even by his standards, Black Man became something unexpected — not just a documentary, but a living archive of Black male interior life.

Jon Covington has always been a storyteller. Whether behind a radio mic, a television camera, or a film lens, his work has carried the same quiet consistency: patience, intention, and a deep respect for human truth. But even by his standards, Black Man became something unexpected — not just a documentary, but a living archive of Black male interior life.

Covington, a Muskegon, Michigan native, never planned to make a film about Black men. The project began as a modest commission: a three-minute video loop meant to accompany a still art exhibit at the Muskegon Museum of Art. A background piece. Something visual to pass the time while visitors waited.

Then the men started leaving the room emotional.

Interviews that were supposed to be brief stretched to nearly an hour. Stories surfaced without warning. One of the earliest participants — Bishop Nathaniel Wells — walked out in tears. That moment changed everything. Covington knew he wasn’t dealing with filler anymore. He was holding something fragile, necessary, and unfinished.

Six years later, Black Man exists in its eighth version — refined, expanded, and finally settled into a form Covington can sit with and say, this is it. The film has traveled far beyond West Michigan, screening in cities like Los Angeles, Washington D.C., Detroit, Baltimore, Austin, and across Florida. What was once local has become communal.

At its core, Black Man dismantles one of the most dangerous myths attached to Black men in America: emotional absence. The idea that Black men do not cry, do not feel deeply, do not break. Covington doesn’t attack the myth head-on — he lets it collapse under the weight of lived experience.

Men in the film speak about fathers, faith, buried trauma, unspoken family truths, and the lifelong pressure to “hold it together.” The consequences of emotional suppression are not abstract here; they are visible. Rage, addiction, incarceration, self-destruction. Covington makes space for the uncomfortable reality that what is never released always finds another exit.

Without intending to, Black Man has become a catalyst for conversations around mental health in the Black community. At one screening, a 36-year-old man stood and said watching the film felt like therapy — the first he’d ever experienced. The documentary gave him permission to seek help. Stories like that are now common, which is why many screenings include mental-health advocates and post-film discussions. The film doesn’t just expose wounds — it points toward healing.

Trust is the documentary’s quiet engine. Covington doesn’t force vulnerability; he earns it. His approach is deceptively simple. Before going deep, he meets people where they are — often starting with something universal, like sports. Comfort comes first. Defenses lower naturally. By the time the real questions arrive, honesty feels less like risk and more like relief.

One interview, in particular, changed Covington himself. Bishop Wells, then in his mid-70s, spoke candidly about his father and an unfulfilled desire to complete something for him — even decades later. Listening to that, Covington realized purpose doesn’t have an expiration date. Wanting more, striving harder, aiming higher isn’t arrogance — it’s permission.

That realization pushed him to confront his own tendency to play small, to self-sabotage, to doubt praise as much as criticism. The film didn’t just document transformation — it caused it.

Audience reactions have been just as revealing. At a Muskegon screening, a predominantly white church group arrived expecting to be the only white faces in the room. Instead, they found hundreds more. Afterward, the response was consistent and disarming: We didn’t know. Not guilt. Not defensiveness. Recognition.

That response speaks to Covington’s larger goal. Black Man isn’t about blame. It’s about humanity. For Black men, the film offers affirmation. For Black women, understanding. For non-Black audiences, a reframing of a group too often flattened by fear and media caricature.

The documentary continues to evolve. New voices. Younger perspectives. Stories once hidden now spoken aloud — including family truths that ripple outward, sparking difficult but necessary conversations far beyond the screen.

There is more coming. Additional films. Possibly a podcast. Maybe even a book. Covington didn’t set out to make this his life’s work — but listening made the decision for him.

Black Man will screen February 26 at the African American Museum in Grand Rapids, Michigan. For Covington, it’s just another stop in a journey he never planned — and one the audience keeps asking him to continue.

To follow the film’s tour and updates, search #BlackManFilm.

Because sometimes the most powerful art doesn’t begin with intention.

It begins with paying attention.

Views: 30